What student engagement looks like:

In a study for Online Learning, Marcia Dixson gives us a snapshot of student engagement in an online class:

Engagement involves students using time and energy to learn materials and skills, demonstrating that learning, interacting in a meaningful way with others in the class (enough so that those people become “real”), and becoming at least somewhat emotionally involved with their learning (i.e., getting excited about an idea, enjoying the learning and/or interaction). Engagement is composed of individual attitudes, thoughts, and behaviors as well as communication with others. Student engagement is about students putting time, energy, thought, effort, and, to some extent, feelings into their learning.

Dixson’s description lines up with the online engagement framework’s five key elements for student engagement: social, emotional, collaborative, cognitive, and behavioral (Redmond, Heffernan, Abawi, Brown, and Henderson 2018). Each of these play a role in designing effective online learning environments for students.

Best ways to increase online student engagement:

Student engagement often involves several types of interactions: student-instructor, student-student, and student-content. Use the tips below to increase your students’ opportunities to interact, collaborate, and participate in your courses.

- Set clear expectations and goals.

As instructors, we are great at setting expectations through syllabi and assignment guides. When we move into online learning spaces, it is important to guide students through not only the course expectations but also the course structure. How did you set up the class in Canvas - by modules? by weeks? Where can students find materials, assignments, and communication tools? How much time should they expect to spend each week on this class? Consider including an introduction module with video tours of your Canvas course.

Remember to review learning outcomes and how they’re connected to activities, assessments, and - when possible - contexts that students will encounter beyond the classroom. What will students be able to do after they take this course? Students are more likely to engage with material when they understand the impact of what they’re studying.

- Use a variety of tools and methods.

Deliver content in bite-sized pieces through different formats: videos, voice-over slides, audio, text, images, etc. Chunking your content in 10-minute segments allows learners to take the content in and process it, making connections between current content and previous work or other contexts.

It's also worth exploring different ways of assessing students and measuring learning objectives. Lucinda Parmer from Southeastern Oklahoma State University has provided Alternatives to the Traditional Exam as Measures of Student Learning Objectives in an article from 2020.

- Build a sense of community.

Use your discussion boards strategically. Harmonize is great for enhancing online discussions because it mirrors popular social media platforms. It provides an easy way for students to respond to posts using images, video, audio, and surveys.

This tool also allows instructors to review students’ participation and flags high and medium-risk students to follow up on.

You might also consider providing feedback to the class on major assignments or discussion posts that seem to have gotten more traction than usual via a video response announcement. Audio comments on assignments also allow students to hear tone better than written comments (just make sure you’ve considered any accessibility issues for the individual students in your class here).

- Incorporate gamification and fun.

The term “gamification” in online learning began picking up traction around a decade ago, but instructors have been incorporating elements of game theory into their classes for much longer. Karl Kapp’s definition - “Gamification is the cover to add the interactivity, engagement and immersion that leads to good learning" - provides a great starting point for thinking about how to incorporate game elements that complement course content. These elements can look like a blend of any of the following: competition and collaboration, a driving narrative, challenges to accomplish, choices along the way, ongoing feedback, and rewards. Visually, they often align with popular game constructs (video games, comic books, D&D campaigns - you get the point), but they don’t have to.

- Empower student choice and voice.

One of the checkpoints for making course content accessible to all students through frameworks like Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is optimizing individual choice and autonomy. According to CAST, the organization that created UDL, one way to do this is to:

Provide learners with as much discretion and autonomy as possible by providing choices in such things as:

- The level of perceived challenge

- The type of rewards or recognition available

- The context or content used for practicing and assessing skills

- The tools used for information gathering or production

- The color, design, or graphics of layouts, etc.

- The sequence or timing for completion of subcomponents of tasks

All of this is contextual, of course. It has to work for your class, your goals, and your students.

- Monitor and adjust your strategies.

Just as you would provide regular feedback to students, consider collecting feedback from your students about what’s working for them and what’s not. This could be something more formal, like an anonymous mid-semester survey, or it could be something as simple as having students include a writer’s memo or a reflection about the content that they’re learning and/or how they’re doing in the class so far. Use this feedback to adjust your approach as necessary.

How can I make sure my courses are engaging?

If you’re interested, you can request that one of the COLRS staff members review your course using the UIS Quality Assurance Rubric. UIS subscribes to Quality Matters (QM), We love the chance to work with you on your courses - from troubleshooting day-to-day issues to thinking through instructional design strategies.

You also might browse these engagement strategies and resources:

Graphic Organizers for Reading

Reading is a skill that we assume most of our students have, but the truth of the matter is that they often need support to ensure they’re reading critically and not passively.

Purpose for reading

In order to offer supports for students when it comes to their reading task, we first need to identify the purpose for reading. In order to do so, we can ask ourselves several questions before we assign a reading task:

- What is meant to be gained from the reading?

- In other words, is this an informational text to provide students with background information on a topic? Will students need to analyze this text in the form of a literary or rhetorical analysis? Is this one of many readings for a synthesis assignment? Thinking about what the students will get out of the reading will help determine how to support them.

- How does their purpose for reading intersect with your purpose as the instructor?

- What next steps will you take in the course after students have read this text? How does this reading support your goals as the instructor? Thinking about your module/unit-level and course-level learning objectives as you assign readings will help you determine how a reading will move the goals of your course forward.

- How does the purpose for reading intersect with the author’s purpose for writing?

- Why was the piece written? At what time were they writing the text? What other events were happening around the time of the piece being written? These questions can help determine places where a student may need more support in order to understand this foundational question; knowing what kind of text their reading will allow them to dig deeper into it.

Once these purposes have been identified, we can ask ourselves, “what support would a student need in order to achieve this purpose for reading?” Those supports can come in the form of graphic organizers.

Types of organizers

Depending on what is meant to be gained from the reading, try some of these organizers:

- KWL Chart: This is a three-column organizer that allows students to consider their prior knowledge and interests before reading, typically for informational purposes. Each letter of KWL stands for:

- K: What students KNOW already (before reading)

- W: What students WANT to know about the topic (before reading)

- L: What students LEARNED about the topic (during/after reading)

- Frayer Model: This organizer is typically used for vocabulary acquisition. The word needing to be defined as a result of reading is at the center, and then students fill out four sections:

- Definition of the term in their own words

- Characteristics of the term

- Examples of the term

- Non-examples of the term

- Though the Frayer Model is typically used in this way, it can be modified for different purposes. For example, if you want students to take a foundational document and make more modern connections, consider having the text at the center of the organizer, and have students make four kinds of connections:

- Text-to-Self: how does this text connect to me/my life?

- Text-to-Itself: how does something I’ve read in this text connect to earlier parts of the text? How is the idea developed?

- Text-to-Text: how does this text connect to other texts I’ve read/watched/listened to?

- Text-to-World: how does this text connect to world events, past or present?

- The Point Loma Nazarene University Center for Teaching and Learning has a number of examples of reading graphic organizers for download. These organizers typically follow set steps:

- What key points are being made in the text?

- What page number is that information found on?

- What insights can be gained from these key points?

- How can I apply these insights?

- Note: There are versions of these organizers that are modified for research and/or peer review!

- Minnesota State University has a number of graphic organizers available for download across many disciplines and for a variety of purposes. Some of these organizers include:

- Compare and contrast: looking and two texts and noting similarities and differences

- Dialogue journals: putting the text in conversation with your own thoughts and ideas about it

- Skimming text organizers: looking for keywords, headers, etc. to gain some insights before diving right into the text

- Diagram a process: based on the reading, create a timeline, flowchart, diagram, etc.

- Quote, Comment, Question format posted in CUNY Writing Fellows is a great format for reader response essays and discussion posts.

- Quotation: Provide a quotation verbatim from the text.

- Comment: In a couple of sentences, state why the quotation is meaningful.

- Question: Is there a word or concept you don't understand? A question you'd like to pose to the author? Does it make you question an assumption or idea?

Luna, Villalón, Martínez-Álvarez, and Mateos (2022) also studied students who were using graphic organizers in a collaborative way, building towards an argumentative synthesis. Through their study, they found that, while students made improvements to their written products with and without the organizers, they made “more in the process intervention.” These organizers could take the form of groups working together to make connections, discussing a text with one another, or taking a section of a text and building off each other.

Impact of using graphic organizers

When graphic organizers are simple and used often, they can improve the ways in which students engage with texts in their courses. Graphic organizers cause students to slow down their reading process, taking reading from being a more passive activity to an active engagement. Depending on the purpose for reading, students can tap into their prior knowledge to build confidence; reflect on their reading before, during, and after reading; and perform high-level metacognitive work.

Using reading graphic organizers doesn’t just improve outcomes when reading; organizers can improve the outcomes of discussion activities and writing tasks–especially writing requiring synthesis of sources.

Lastly–and perhaps most importantly–using reading graphic organizers is a learner-centered approach to assessing students’ reading comprehension and understanding. It gives them the opportunity to create an artifact that they can revisit and build on throughout their time in the course, while still providing the instructor with the opportunity to assess students and hold them accountable for the reading they’re doing.

As always, we would love to see how you’re using graphic organizers for reading in your courses! Feel free to email COLRS at colrs@uis.edu to share what you’re doing with your classes. And if you want to implement these strategies into your own course and need help doing so, reach out to our office anytime!

Discussion Prompt Design

Variety is the spice of online discussions

We’ve likely all been there – setting up our discussions for the semester and stuck in an instructional rut: “Respond to this article and reply to two peers.” After several weeks, it can feel a bit boring, even to us as instructors. While a consistent course organization and predictable due dates do promote student success in online courses, we should feel confident in mixing up the format of assignments to add some variety.

Rich and engaging discussions are often the heart of an online course, and for good reason. They engage students both socially and intellectually. Research tells us that both types of types of engagement are necessary for students to be successful and feel engaged in online courses.

In the literature, scholars have been able to link social interaction to engagement and satisfaction in online courses. Interactions with other students and with instructors improves student satisfaction with courses and their perceived amount of learning in a course. (Gherghel et al., 2023; Jung & Choi, 2002; Kuo et al., 2014; Swan, 2001, 2002; Wang et al., 2022) Cho & Cho (2014) found that they could predict behavioral and emotional engagement in an online course based on teaching presence and whether instructors scaffolded student-to-student and instructor-to-student interactions.

Discussions are a great platform to scaffold for these key interactions. Below, we share some ideas for spicing up your discussions.

Why spice up discussion prompts?

- Critical Thinking and Problem Solving: Varied prompts can encourage critical thinking and problem-solving skills, rather than just summarizing.

- Real-world Relevance: Create prompts that reflect real-world situations and scenarios to make the course content more relevant to students. It helps them connect theoretical knowledge to practical applications, fostering a deeper understanding.

- Motivation and Engagement: Repeating the same type of discussion prompt can become monotonous and demotivating for students. Varied prompts keep the learning experience fresh, motivating students to participate actively and stay engaged throughout the course.

- Inclusivity: Students have different backgrounds, experiences, perspectives, and strengths. Create discussion opportunities for all students to contribute and share their unique viewpoints, ensuring inclusivity and diversity in discussions. Some may excel in written discussions, while others may prefer the opportunity for audio or video-based responses. Appeal a variety of strengths and maximize student participation and connection by providing a variety response options.

- Higher-Order Thinking: Some prompts can stimulate higher-order thinking skills like analysis, synthesis, and evaluation.

- Active Participation: By changing the format and type of discussion prompts, instructors can encourage more active participation. Some students may be more comfortable with group discussions, while others may prefer individual reflections or peer evaluations.

- Reduce Cheating: Using varied prompts with specific requirements makes it more challenging for students to rely on external sources or generative AI, thereby reducing the likelihood of cheating.

Examples of Varied Discussion Prompts

By using a combination of these discussion prompts, you can create a dynamic and engaging learning environment that encourages students to think critically, apply their knowledge, and actively participate in the online course. Adapt these examples to suit your course's specific objectives and content.

Open-Ended Questions:

- "What are the key takeaways from this week's reading?"

- "How does the concept we discussed relate to real-world situations?"

Case Studies:

- "Analyze the provided case study and propose a solution to the problem presented."

- "Discuss how the concepts we've learned can be applied to the scenario in this case study."

Debates:

- “Take a stance on a controversial topic related to the course material and defend your position. Engage with your peers who hold opposing views."

- "In a structured debate, argue for or against a specific theory or approach we've covered."

Peer Reviews:

- "Share your project or essay draft with a peer and provide constructive feedback on their work."

- "Reflect on the feedback you received from your peer review and describe how it has influenced your revision process."

Reflective Journals:

- "Write a reflective journal entry on your personal experiences applying the concepts from this module in your daily life or work."

- "Discuss how your perspective has evolved throughout the course and what you've learned about yourself as a learner."

Scenario-Based Questions:

- "Imagine you are a [relevant profession], and you encounter a specific situation. How would you handle it based on what you've learned in this course?"

- "Create a scenario where the principles of [course topic] are essential and discuss its potential impact."

Current Events:

- "Find a recent news article or event related to the course material and discuss its implications."

- "How do current global events reflect or challenge the theories discussed in this course?"

Group Discussions:

- "Work in groups to analyze a complex problem and present your findings and solutions to the class."

- "Collaborate with your group to create a multimedia presentation on a course-related topic and discuss the challenges you faced and how you overcame them."

Ethical Dilemmas:

- "Explore an ethical dilemma related to the course material and discuss the moral and ethical considerations involved."

- "What ethical issues might arise in the application of [course concept]? How can these be addressed?"

Hypothetical Scenarios:

- "Imagine a world without [key concept]. How would society function differently?"

- "Create a hypothetical business plan or project proposal that integrates the principles discussed in this course."

Tech Tools to Support Robust Discussions

Harmonize Discussions in Canvas

Many UIS faculty members are using a tool called Harmonize to enhance the online discussion features in Canvas. Harmonize allows you to:

- Add multiple due dates to a discussion

- Easily integrate multimedia

- Auto-grade participation

- Add image and video annotation

- Add polls to discussions

- Create student-led discussions

- The Comment Library allows instructors to save and reuse commonly used text feedback in SpeedGrader.

- As an instructor, you can add new comments and delete existing comments.

- Comments you have added to the Comment Library are accessible from each course in which you are enrolled as an instructor.

More Information

- 5 New Twists for Online Discussions(link is external)

- Active Learning Instructional Strategy: Discussion Board Prompts

- “Planning and Facilitating Quality Discussions” ACUE webinar on the NIU page on Effective Online Instruction Webinars

- Successful Strategies for Creating Online Discussion Prompts.

- CREST+ Model: Writing Effective Online Discussion Questions by Lynn Akin and Diane Neal

References

Cho M.H., Cho Y. (2014). Instructor scaffolding for interaction and students' academic engagement in online learning: Mediating role of perceived online class goal structures. The Internet and Higher Education.

Gherghel, C., Yasuda, S., & Kita, Y. (2023). Interaction during online classes fosters engagement with learning and self-directed study both in the first and second years of the COVID-19 pandemic. Computers & education.

Jung I., Choi S. (2002). Effects of different types of interaction on learning achievement, satisfaction and participation in web-based instruction. Innovations in Education & Teaching International.

Kuo Y.C., Walker A.E., Schroder K.E.E., Belland B.R. (2014). Interaction, internet self-efficacy, and self-regulated learning as predictors of student satisfaction in online education courses. The Internet and Higher Education.

Swan K. (2001). Virtual interaction: Design factors affecting student satisfaction and perceived learning in asynchronous online courses. Distance Education.

Swan K. (2002). Building learning communities in online courses: the importance of interaction. Education, Communication & Information.

Wang Y., Cao Y., Gong S., Wang Z., Li N., Ai L. (2022). Interaction and learning engagement in online learning: the mediating roles of online learning self-efficacy and academic emotions. Learning and Individual Differences

Kaltura Video Quizzing

Kaltura offers the option for instructors to integrate low-stakes objective quizzes on videos that are used in courses. Paired with shorter videos (around 5-10 minutes), the quizzing option offers the possibility for increased student engagement and encourages students to watch videos all the way through.

In order to create a Kaltura Video Quiz:

- Click on Account in the blue menu on the left, then go to My Media in the navigation menu.

- Click Add New, and then select Video Quiz.

- You will be taken to the Editor / Media Selection page, where you can either select an existing video or upload a new one.

- To upload a new one, click the Upload Media button

- To use an existing video, scroll through the list and click Select next to the one you want to use for the quiz.

- To upload a new one, click the Upload Media button

- From here, a window will open within your current tab where you can create your quiz questions. The quiz tool will allow you to insert questions into the video at specific intervals using the highlighted timeline tool, and you can also edit the description and grading information for the quiz. This help document from Kaltura details the quiz creation and editing process, including screenshots.

- When you are finished adding quiz questions and updating the settings, click Done. The video quiz will now be available in My Media and can be added to a Canvas course, just like any other video hosted in Kaltura.

- If you wish to integrate your Kaltura video quiz into the Canvas grade book, you will need to create a new Canvas assignment in a module or on your Assignments page in your course.

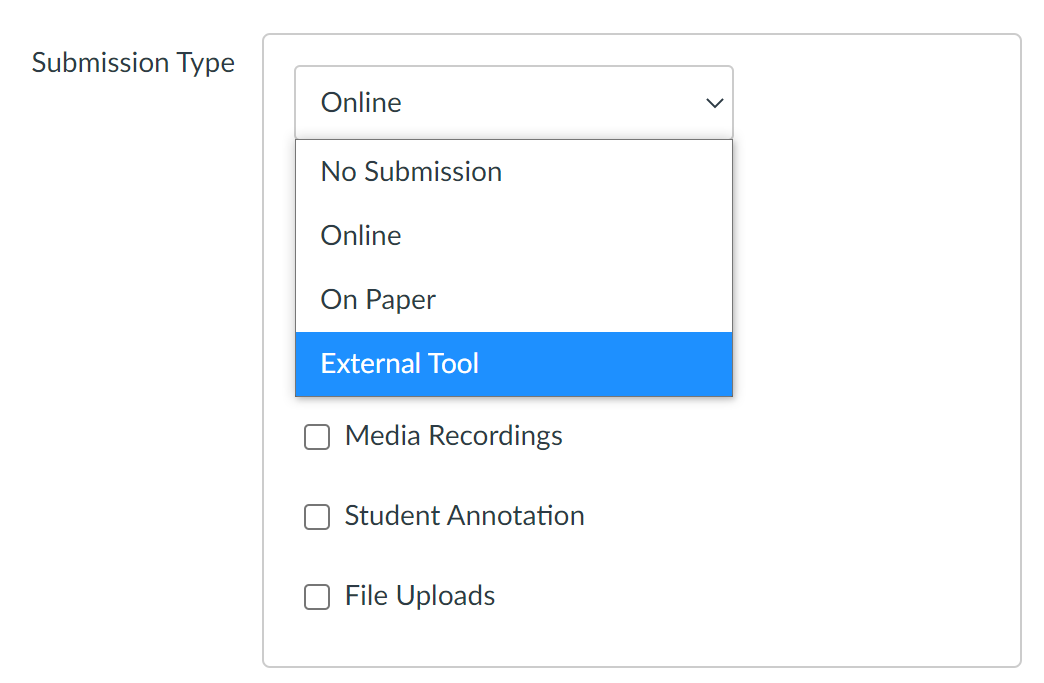

- When creating an assignment, for Submission Type, select External Tool.

- Click the Find button.

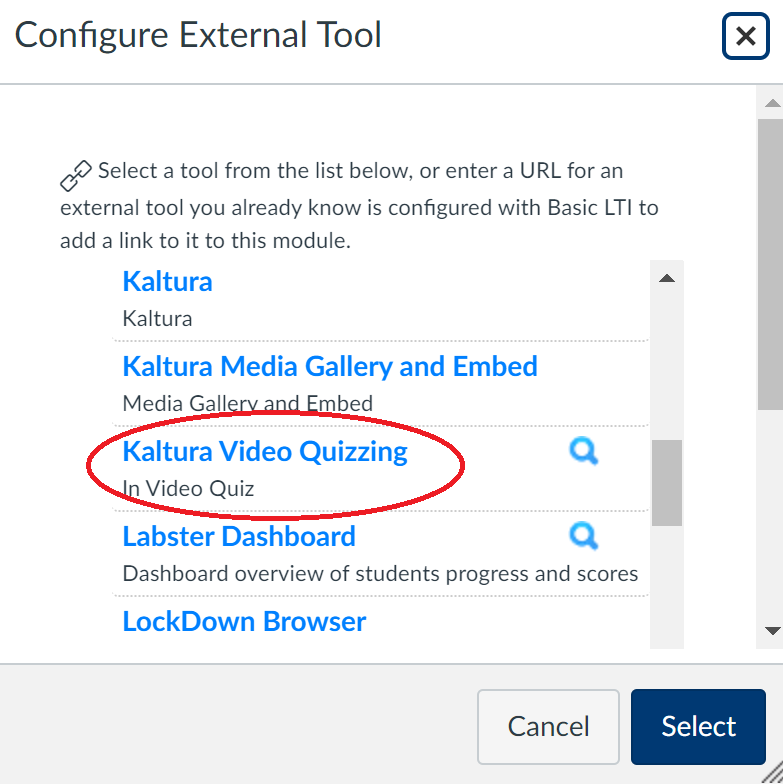

- Scroll down until you see Kaltura Video Quizzing, and select it.

- Your My Media page will load in a small window within the tab, and a list of your available video quizzes will appear. Select a video quiz to use. This will take you back to the Configure External Tool page. Click Select to confirm your choice.

- Scroll to the Points field. Enter the total point value for your Kaltura Quiz.

- Click Save & Publish to make the assignment available for your students.

There are several important points to keep in mind:

- As a best practice, COLRS does not recommend this tool for high-stakes exams.

- This feature is not compatible with Respondus Monitor or Examity.

- Only objective (true/false or multiple choice) questions are gradable. Open questions and reflection points are not considered gradable and will not be counted in your students' scores.

- Kaltura treats each gradable question (true/false or multiple choice) as equal in value and will divide the total point value for the quiz by the number of gradable questions. For example, in a 10-point quiz with 2 gradable questions, each question will be worth 5 points.

Student-Created Videos

Assignments that ask students to create video presentations can be excellent methods to assess the synthesis of course materials or to present original research.

Best Practices for Student Video Submissions

Students have access to record and share videos through Kaltura Media, the UIS video creation and storage solution. Student video projects can be created in Kaltura Media or created elsewhere and uploaded to Kaltura Media. Students may share the videos by:

- Submitting a URL (weblink) to the video to a Canvas Assignment,

- Embedding their video in a text box, or

- Adding a link to the video or embedding the video in a Canvas Discussion

Create a Canvas Assignment for Student Video Submission

- Click on "Assignments" from the course navigation.

- Click "+Assignment" in the top right corner.

- Name your assignment.

- Enter a description or assignment details in the rich content editor (RCE). Be sure to include instructions for how your students can embed or link to their Kaltura Media video.

- Go through the assignment settings and make any changes you want to make to categories like "points," "assignment group," etc.

- For Submission Type, select Online, then choose one of the following options:

- Text Box: Choose if you want students to embed their Kaltura video for you to view. This submission method doesn't involve extra steps for your students to locate the Kaltura URL.

- Website URL: Choose this option if you want students to provide a URL to the video on Kaltura, YouTube, or other video-sharing platforms.

- Once all of your assignment settings are how you'd like for them to be, click Save & Publish to allow students to see the assignment. You can also click Save to keep it hidden from students for the time being.

Video Submissions to a Canvas Discussion Board

By default, students will be able to embed Kaltura Media videos in a discussion post. Follow these directions to create a Canvas Discussion. Be sure to include instructions for how your students can embed or link to their Kaltura Media video in their posts.

Excelsior Online Writing Lab (OWL)

The Excelsior Online Writing Lab (OWL) is a highly-interactive, publicly-available, and media-rich online writing lab designed to help students make the transition to college-level writing. In 2014, the Excelsior OWL - ESL Writing Online Workshop (WOW) won the 2013 Distance Education Award by the National University Technology Network (NUTN).

The Excelsior OWL offers videos, interactive PDFs, video games, quizzes, Prezis, and more!

Home Page and Learning Areas

From the Excelsior OWL Home Page, you can access all of the learning areas, as well as "Additional Resources" (found in the header) and "Acknowledgements" (found in the footer).

Each learning area has its own landing page, with access to the content, as well as the "How to Use OWL" and "Additional Resources" pages. Depending on the learning area, there may be additional options available on the landing page.

Page Navigation: How to Use the OWL

The OWL provides information on how to use the Excelsior OWL website. Generally, once inside a learning area, you will see the online writing lab menu on the left side of the screen. The active learning area is highlighted, at which point all of the topics for that learning area are displayed below it. some of the topics have multiple sections.

Quizzes

The built-in quizzes allow students to check their understanding of a particular section of the OWL. Examples include a paraphrasing quiz, a punctuation quiz, and a digital writing quiz.

ESL-WOW

For ESL students using the ESL-WOW area of the OWL, they will learn to:

- Generate ideas

- Develop a thesis

- Map ideas

- Revise their work

- Cite specific and relevant evidence

- Edit and polish their writing for submission

Ideas for Using the Excelsior OWL for Online or Blended Classes

If you're interested in sharing this resource with your students, consider the following suggestions:

- Send students to individual links within the OWL.

- For example, if students are to provide an annotated bibliography, provide a link to the Annotated Bibliography page. The Literature Review section is another example, which also includes a Prezi.

- Refer students back to the OWL in your feedback.

- For example, if the student has provided a weak thesis statement, you may provide a link to the Thesis section, or a specific section (such as Stating your Thesis) within the Thesis section.

- Support student understanding of plagiarism.

- The Avoiding Plagiarism section of the OWL provides a thorough overview of the topic of plagiarism. With audio, video, and supporting documentation, students will develop a keen understanding of what constitutes plagiarism and how to avoid it. The pre-test and post-test provide a method for students to track their progress.

"Thinking Aloud" Strategy

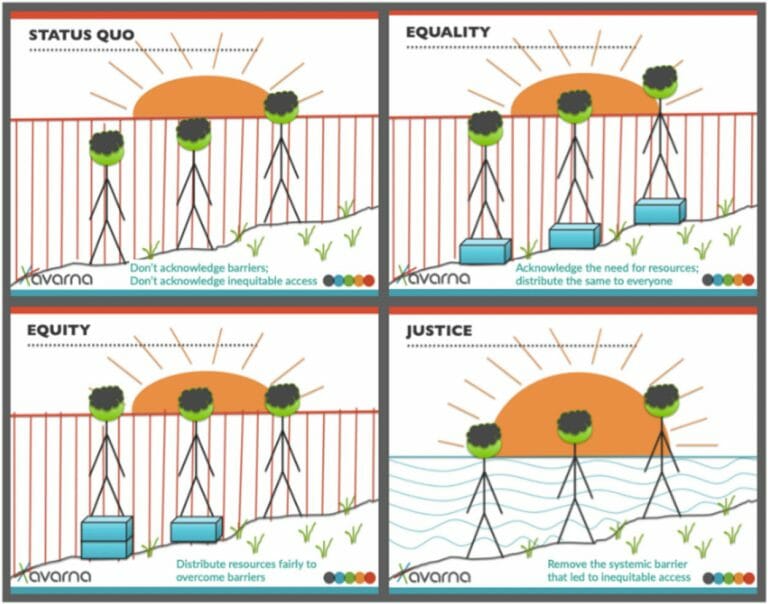

The increase in online, hybrid, and remote learning has, in many ways, required all of us at UIS to think more about new tools and teaching strategies to reduce barriers and increase access for all our students, especially those who come from underrepresented or disadvantaged backgrounds. In our continual efforts to bring equity and justice to our students, and to help in their academic success, one potentially useful pedagogical strategy is called think aloud.

According to Dr. Eugene Allevato from Woodbury University, "Think aloud is a strategy that enhances students' comprehension and intellectual growth by removing . . . barriers. By expressing one's thoughts while reading, students develop their reading skills because they can acquire information from what they read, add to their knowledge, enlarge their way of thinking and reasoning to advance toward academic excellence. In addition, this strategy provides a better way to assess students' learning." You can find this full article on Academic Impressions.

Reflection & Learning Transfer

At the start of term, we spend a lot of energy planning the first interactions of a course and setting our students up for successful learning – introductions, building community, and understanding outcomes and expectations. Our choices at the end of the term are just as important. Summarizing, reflection, and making connections to the bigger picture are critical for long-term transfer of learning, or applying learning from one situation to a completely different context.

Reflective activities are also an important aspect of culturally responsive teaching. Rhodes and Schmidt (2018), provide a Motivational Framework of Culturally Responsive Teaching with four elements to consider as you develop activities for your courses.

Below, you’ll find strategies to encourage long-term transfer of learning for your students. Consider trying out one strategy this spring term!

Summarizing Key Points

- Record a reflection video for your course. You could discuss what you see as the key takeaways for the term. Another approach would be to do a walk through of the syllabus and reflect on how they built knowledge and skills in the subject area over time. Connect the skills to their future work.

- Course concept maps. Ask students to create a concept map that represents their learning for the term. To extend this activity to “connecting to the big picture,” ask students to connect each concept to different areas where the concepts may be applicable.

Reflecting

“We do not learn from experience. We learn from reflecting on experience.”

– John Dewey (1933)

Reflection, or metacognition, is the ability to “understand and monitor one’s own thoughts and the assumptions and implication of one’s activities” (Lin 2001, 23). John Dewey introduced the idea of reflection to the field of education in 1933. Dewey focused on reflection as the key component of experiential learning, stating, “We do not learn from experience. We learn from reflecting on experience.” Students need to actively reflect on their experiences in order to create meaning and grow. Brock University’s Role of Reflection page contains excellent summaries of frameworks for reflection as well domains for reflection. Several ideas are presented in the open textbook Reflecting with a Purpose (2021).

- What? So what? Now what? This three part reflection activity asks students to reflect, assess value, and look to the future. This activity could be a small debrief after an activity or about the entire course.

- Create a meme and reflect. Ask students to create a meme that represents an aspect of their learning in a course. Have them post their meme along with a short explanation to a discussion and respond to a peer. Creating memes can be a fun activity for a class, and it is also a great opportunity to include a lesson on digital Blackface to help raise student awareness of racist stereotypes in social media.

- Letter to a future student. Have current students write advice to future students. Learn more from Babino and Riley’s article in The Scholarly Teacher.

- Journaling. Building a reflective practice into your course will help your students develop metacognitive skills. Harmonize discussions in Canvas can be set up between individual students and instructors to allow an easy journaling format. Requiring a weekly or bi-weekly journal entry entry can open dialogue between instructors and students. Be sure to provide optional prompts for students who are uncomfortable with reflection.

- Did students have conceptions that changed?

- How can their learning be applied in their lives?

- What new questions do they have in the subject matter or discipline?

Connecting to the Big Picture

- 5 big ideas. Have students post their suggestions of the five big ideas in the course and post them to a group discussion board. Ask the groups to work together to come to a consensus and post their work on a Canvas page to share their ideas. Base a class discussion on the compiled page. Ask each student to reflect on what surprised them or interested them. Adapted from O’Hara at UC Berkeley.

- Video wrap-up. Ask students to record a video that reflects their learning for the term and connects it to their future goals or other situations they are facing. They can use a cell phone, Kaltura Media screen capture (from UIS and available through Canvas), or other tools to record their ideas. Give them a few options to reflect on, such as:

- What is the most significant or surprising thing you learned?

- How has your understanding grown or changed over the course of the semester?

- Which readings, topics, or activities were most helpful? How so?

- To what extent have you met the course outcomes?

- What did you hope to learn in this course? Did you meet your learning goals?

Resources

- What Is ‘Transfer of Learning’ and How Does It Help Students?

In this Education Week video, Larry Ferlazzo talks about five strategies to encourage transfer of learning. - Three Ideas for Implementing Learner Reflection by Li-Shih Huang in Faculty Focus

- Role of Reflection from Brock University

References

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the education process. Boston, MA: D. C. Heath.

Lin, X. (2001). “Designing metacognitive activities.” Educational technology research and development, 49(2): 23-39.

Rhodes, Christy & Schmidt, Steven. (2018). Culturally Responsive Teaching in the Online Classroom. eLearn, November 2018.