A team of researchers has developed a straightforward yet powerful method to predict how hot it feels on city streets, offering a new tool to help communities combat the growing threat of urban heat. The study, led by Dr. Kyle Blount from the University of Illinois Springfield, shows that by combining high-resolution aerial imagery with simple surface and air temperature data, it’s possible to accurately estimate air temperatures at the street level in residential neighborhoods.

Urban heat islands—areas where cities become significantly warmer than surrounding rural areas—pose serious health risks, especially during heatwaves. But predicting exactly where and how hot it gets in different parts of a city has been a major challenge. Traditional satellite data often misses key details, like the cooling effects of tree shade, while ground-based surveys are time-consuming and expensive.

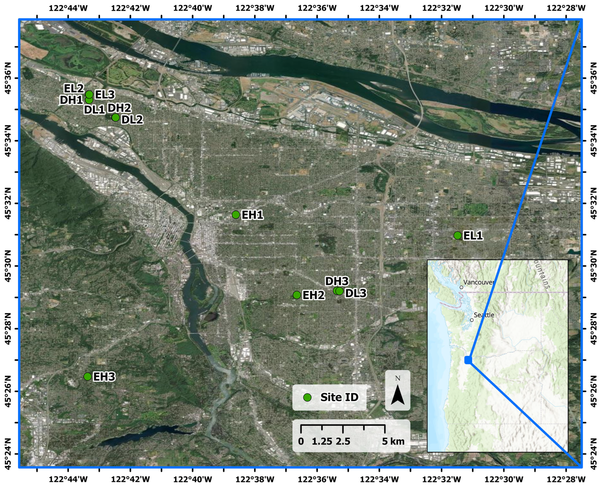

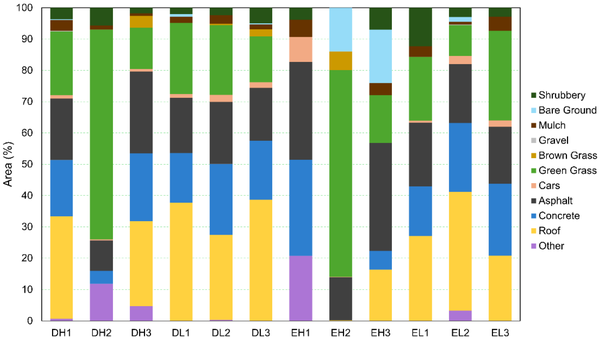

To bridge this gap, the researchers tested a new approach in 12 neighborhoods across Portland, Oregon. They used ground-based thermal cameras to measure how hot different surfaces—like asphalt, grass, and rooftops—get in both sun and shade. Then, using detailed aerial images, they calculated how much of each surface type was present in each neighborhood and how much of it was shaded.The result was a “mosaic” of surface temperatures that reflected both land cover and shading. When they compared these mosaics to actual air temperature readings taken in shaded areas, the match was striking—almost a perfect 1:1 correlation.

One of the most surprising findings was that even sunlit surfaces in tree-lined streets were cooler than similar surfaces in less shaded areas. This suggests that partial shading throughout the day, not just full shade at one moment, plays a major role in keeping neighborhoods cooler.

The method is simple enough to be used by city planners, public health officials, and community groups without needing advanced modeling or expensive equipment. It could help cities identify heat-vulnerable areas, plan tree planting efforts, and design cooler, more livable neighborhoods.

As climate change continues to drive up temperatures, tools like this could be key to protecting public health and improving urban resilience.